Violence, including bullying and other types of behaviors, has seen increased political and scientific attention over the past years. However, this behavior among younglings and schools has declined over the past decade; the abuse of children by other children in school settings remains as one of the major issues of concern among adults and communities. In response, a number of intervention programs have been developed to help reduce the amount of bullying and violence in schools. Results suggested a significant effect for anti-bullying programs. However, as expected, some of the results seemed to fall under some sort of publication bias and did not meet the necessary objectives for practical significance. Publication bias (or the “file drawer effect”) occurs when articles with statistical significance are selected for publication more often than are articles that do not obtain significance (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991).

Another point of impact is that even though the effect for programs targeted to bullied people are slightly better, this type of research produce little to no effect on young participants. Thus, anti-bullying programs may not bring such an impact due to its lack of credibility.

Violence in schools brings increase the continuance of the bullying behavior to more serious violence, is an issue that has been attracting educators, scientists, politicians, and the public over the past decade (Phillips,2007). Nowadays, the perception of children not being able to understand what they are doing and that they do not hold malice against their peers stopped being viewed as innocent. Moreover, research disputes this common assumption that children are innocent (Phillips, 2007), and recent literature has documented that lesser forms of violence, such as bullying, are common among children (Nansel, Overpeck, Pilla, Ruan, Simons-Morton, & Scheidt., 2001). In addition to this common assumption a multitude of school anti-bullying programs have been developed, but it is uncertain whether these programs can reach success in achieving their intended outcomes. This uncertainty may be due to many anti-bullying programs having not been subjected to systematic and empirical review, or could it be that we still do not know how to evaluate bullying?

Most schools have implemented bullying prevention programs, and used high amounts of money to create safer school environments (Sherman, 2000). However, with the limited knowledge of anti-bullying programs’ success, parents, schools, and communities fall into the idea the they are addressing the problem when the resources committed to such efforts could be better used to develop more effective programs (Farrell, Meyer, Kung, & Sullivan, 2001).

Bullying as a Problem Behavior

Violence in schools brings increase the continuance of the bullying behavior to more serious violence, is an issue that has been attracting educators, scientists, politicians, and the public over the past decade (Phillips,2007). Nowadays, the perception of children not being able to understand what they are doing and that they do not hold malice against their peers stopped being viewed as innocent. Moreover, research disputes this common assumption that children are innocent (Phillips, 2007), and recent literature has documented that lesser forms of violence, such as bullying, are common among children (Nansel, Overpeck, Pilla, Ruan, Simons-Morton, & Scheidt., 2001). In addition to this common assumption a multitude of school anti-bullying programs have been developed, but it is uncertain whether these programs can reach success in achieving their intended outcomes. This uncertainty may be due to many anti-bullying programs having not been subjected to systematic and empirical review, or could it be that we still do not know how to evaluate bullying?

Most schools have implemented bullying prevention programs, and used high amounts of money to create safer school environments (Sherman, 2000). However, with the limited knowledge of anti-bullying programs’ success, parents, schools, and communities fall into the idea the they are addressing the problem when the resources committed to such efforts could be better used to develop more effective programs (Farrell, Meyer, Kung, & Sullivan, 2001).

Bullying as a Problem Behavior

| Coming to an agreement on what is the precise definition of bullying has yet to be reached. This not only complicates research but also complicates how the research is measured. Some researchers focus on studying specific forms of bullying such as acts inflicted because of race and/or gender, and others have focused on maturational differences among youth (Kyriakides, Kaloyirou, & Lindsay, 2006). |

Regardless of definitional constraints, affected people are more likely to have a negative perception of their school (Nansel et al., 2001), behavior problems (Haynie, Nansel, & Eitel, 2001), and difficulty concentrating on schoolwork (Sharp & Smith, 1994). Is it that bullying brings other types of problems such as: learning disabilities?

Other research adds that victims receive lower grades and avoid certain areas and activities (DeVoe et al., 2005). In addition, some victims of this form of violence tend to experience stress-related symptoms such as headaches and nightmares, whereas others suffer from depression and school phobia (Sharp & Smith, 1994). Research has also shown that bystanders or witnesses to acts of bullying may also experience similar problems (Kyriakides et al., 2006). With respect to bullies, there is evidence that has shown that their likelihood to engage in criminal activity as young adults is much higher than their less aggressive peers (Bollmer, Harris, & Milich, 2006; Heydenberk, Heydenberk, & Tzenova, 2006), although, according to Olwus, 1995, bullies may evidence fewer mental health and social problems than was once thought whereas less aggressive people might present higher tendencies of agitation (Fishkind, A. 2002).

Programs Designed to Prevent Bullying

Anti-bullying programs in schools are as diverse as the definitions constructed to understand this form of violence. More traditional anti-bullying programs follow the Olweus model. The Olweus Bully Prevention Program is designed to help identify bullies, in elementary, middle, and high schools, and to help them as well as their victims cope with the effects of this type of school violence. The Second Step Violence Prevention Program is also a classroom-based program that has shown some success in improving social competence and reducing anti-social behaviors (Taub, 2001) as well as decreasing aggression (Van Schoiack-Edstrom, Frey, & Beland, 2002). Moreover, Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP) teaches students social skills and how to respond to different problems that might affect they everyday activities (Farrell, Meyer, Sullivan, & Kung, 2003; Farrell, Meyer, & White, 2001).

More recent programs have approached this problem from a restorative justice model, which tries to restore the relationship between the victim and the offender by using the reintegrate shaming techniques proposed by Braithwaite (1989), as well as forgiveness and reconciliation, to reduce incidents of bullying (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2006).However, is it possible that shaming techniques might have a negative influence on bullies and thus, increase the level of aggression? Moreover, researchers are exploring the role of biological processes and, more specific, the role that hormones play in the ability of youth to mediate conflict (Hazler, Carney, & Granger, 2006).

Other research adds that victims receive lower grades and avoid certain areas and activities (DeVoe et al., 2005). In addition, some victims of this form of violence tend to experience stress-related symptoms such as headaches and nightmares, whereas others suffer from depression and school phobia (Sharp & Smith, 1994). Research has also shown that bystanders or witnesses to acts of bullying may also experience similar problems (Kyriakides et al., 2006). With respect to bullies, there is evidence that has shown that their likelihood to engage in criminal activity as young adults is much higher than their less aggressive peers (Bollmer, Harris, & Milich, 2006; Heydenberk, Heydenberk, & Tzenova, 2006), although, according to Olwus, 1995, bullies may evidence fewer mental health and social problems than was once thought whereas less aggressive people might present higher tendencies of agitation (Fishkind, A. 2002).

Programs Designed to Prevent Bullying

Anti-bullying programs in schools are as diverse as the definitions constructed to understand this form of violence. More traditional anti-bullying programs follow the Olweus model. The Olweus Bully Prevention Program is designed to help identify bullies, in elementary, middle, and high schools, and to help them as well as their victims cope with the effects of this type of school violence. The Second Step Violence Prevention Program is also a classroom-based program that has shown some success in improving social competence and reducing anti-social behaviors (Taub, 2001) as well as decreasing aggression (Van Schoiack-Edstrom, Frey, & Beland, 2002). Moreover, Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP) teaches students social skills and how to respond to different problems that might affect they everyday activities (Farrell, Meyer, Sullivan, & Kung, 2003; Farrell, Meyer, & White, 2001).

More recent programs have approached this problem from a restorative justice model, which tries to restore the relationship between the victim and the offender by using the reintegrate shaming techniques proposed by Braithwaite (1989), as well as forgiveness and reconciliation, to reduce incidents of bullying (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2006).However, is it possible that shaming techniques might have a negative influence on bullies and thus, increase the level of aggression? Moreover, researchers are exploring the role of biological processes and, more specific, the role that hormones play in the ability of youth to mediate conflict (Hazler, Carney, & Granger, 2006).

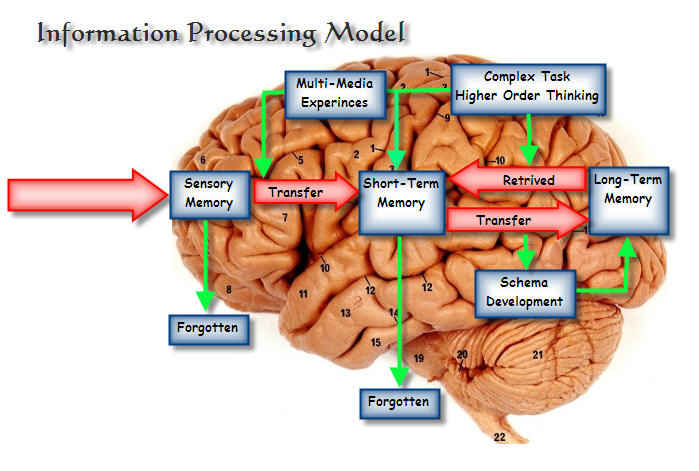

| There is also research on understanding individual coping mechanisms, how students process information and interpret diverse situations, and how they use their past experiences to deal with aggression. Literature suggests that aggressive children tend to interpret situations and environment differently from nonaggressive peers. Bullies are also considered “deficient in their social intelligence and in their ability to interpret and manage information deriving from social interactions with peers” (Gini, 2006) and thus tend to respond with aggressive behavior. |

However, literature also suggests that bullies are “skilled social manipulators that lack the empathic reactivity towards victims’ suffering” (Gini, 2006). Thus, programs that focus on the cognitive and emotional dimensions of bullying as well as moral sensitivity and appropriate empathic reactivity have also been implemented in schools (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006).

Essentially, depending on the approach, anti-bullying programs can bring a number of elements ranging from the impletion on how deal with aggression, pedagogy within the school to individual counseling for the behavior shown, which often can involve the juvenile justice system (Phillips, 2007). Phillips (2007) also suggests programs that hold society accountable for bullying. Because “masculinity and male violence are primarily socially constructed – is it bullying only male students experience? Thus, he proposes that “we should hold society accountable both for the development of norms that are not healthy and for the violent practices that affirm them”. Although there are many other programs, it is imperative to be able to decide which are most effective and jumping to conclusions such as shaming techniques are successful and male violence is primarily social should be avoided. Thus, the purpose of this study is not to provide a review of each anti-bullying program implemented in the United States (Nansel et al., 2001; Olweus, 1995; Olweus et al., 1999) but to provide a constructed criticism to what others have analyzed regarding the effectiveness of these programs in general.

Analyses of School Violence Prevention Programs

Christopher J. F., Claudia SM, John K., JR and Patricia S. (2007) conducted a research on all the articles published regarding bullying between the years of 1995 and 2006. They used a special criteria which included topics bullying intervention, prevention, treatment or therapy (please see pg. 12 for more details on the criteria and tables used on this study). A total of 42 published articles were found. Under their results they found that the effect of anti-bullying programs on violent or broader bullying outcomes was positive and significant. However, they argued that as meta-analyses emphasize on pooled sample size, the mentioned that the statistical significance in and of itself was not meaningful. Of greater concern is the interpretation of the effect size of the outcome (Cohen, 1994). They interpreted their results as indicating the effect of anti-bullying programs is positive in the population, but the size of the effect is minimal. Moreover, they found that the impact of these programs is less for low risk children with a 1% impact and higher for high risk children with a 3.6% impact. Therefore, we can conclude that even though anti-bullying prevention programs bring a slight portion of positive results they are still rather unnoticeable. Results were best for programs that specifically targeted high-risk youth, although even here, the overall effect size was small.

Essentially, depending on the approach, anti-bullying programs can bring a number of elements ranging from the impletion on how deal with aggression, pedagogy within the school to individual counseling for the behavior shown, which often can involve the juvenile justice system (Phillips, 2007). Phillips (2007) also suggests programs that hold society accountable for bullying. Because “masculinity and male violence are primarily socially constructed – is it bullying only male students experience? Thus, he proposes that “we should hold society accountable both for the development of norms that are not healthy and for the violent practices that affirm them”. Although there are many other programs, it is imperative to be able to decide which are most effective and jumping to conclusions such as shaming techniques are successful and male violence is primarily social should be avoided. Thus, the purpose of this study is not to provide a review of each anti-bullying program implemented in the United States (Nansel et al., 2001; Olweus, 1995; Olweus et al., 1999) but to provide a constructed criticism to what others have analyzed regarding the effectiveness of these programs in general.

Analyses of School Violence Prevention Programs

Christopher J. F., Claudia SM, John K., JR and Patricia S. (2007) conducted a research on all the articles published regarding bullying between the years of 1995 and 2006. They used a special criteria which included topics bullying intervention, prevention, treatment or therapy (please see pg. 12 for more details on the criteria and tables used on this study). A total of 42 published articles were found. Under their results they found that the effect of anti-bullying programs on violent or broader bullying outcomes was positive and significant. However, they argued that as meta-analyses emphasize on pooled sample size, the mentioned that the statistical significance in and of itself was not meaningful. Of greater concern is the interpretation of the effect size of the outcome (Cohen, 1994). They interpreted their results as indicating the effect of anti-bullying programs is positive in the population, but the size of the effect is minimal. Moreover, they found that the impact of these programs is less for low risk children with a 1% impact and higher for high risk children with a 3.6% impact. Therefore, we can conclude that even though anti-bullying prevention programs bring a slight portion of positive results they are still rather unnoticeable. Results were best for programs that specifically targeted high-risk youth, although even here, the overall effect size was small.

Conclusion

School-based anti-bullying programs are not practically effective in reducing bullying or violent behaviors in the schools. This conclusion is likely to be disappointing for teachers, parents, and communities given the increased interest in targeting bullying and other violence in the schools. Given the noble, yet disappointing goal of reducing violence in the schools and the enormous financial and research effort devoted to developing anti-bullying programs, it would be useful to consider why these programs demonstrate such limited effectiveness. Are we seeing bullying differently, or is it that (as explained on previous papers) we facing the problem from a different perspective? Do we need to review what a bully is and how do they start even though research show that toddlers are naturally aggressive? Donald Herb (1997) and Tremablay & Nagic (2005). Several explanations are offered here, although further research would be necessary to truly understand this yet “inexplicable” behavior.

The first suggestion is that bullying, in particular (as opposed to more serious violence), is more advantageous to bullies than is nonbullying – we should understand this as bullying and “prevention” programs could possibly foster more violence behaviors rather than halting them. They might not be shown at school due to the consequences students might face, but this may transfer to outside violence. Although bullies are still perceived as insecure and, in effect, victims of their own aggression, research has suggested the opposite, yet some are still against this finding because research has also shown that some people might be seen hide themselves into projections of what they would like to be. On Carney (2010) words: “powerful people are better liars”. Here findings showed that powerful people shoulder shrugged less than less-powerful people.

Aside from aggressive and dominant personality traits, bullies have high self-esteem and are effectively normal children (Olweus, 1995). Bullying and violent behavior may, in many cases, be an effective strategy in climbing the dominant society among children at the expense of other children. As anti-bullying programs may encourage equality in problem solving that would involve bullies reducing their social dominance, there may simply be no incentive offered by these programs to attract bullies or violent children to follow them or be encouraged to participate in such activities. In other words, anti-bullying programs seem to only benefit victims by “halting” aggressive, and thus how are we really helping victims and more importantly what is happening with the aggressive peers is the are not incentivized for participating? As bullies or violent children see no personal benefit in following the program recommendations, they simply reject them. Nonviolent children are often seen trying to follow the program suggestions but may become frustrated when violent children do not. Thus, without effective incentives for bullies, there is little reason to believe that these programs are succeeding.

In conclusion, this study tried to examine the effects of school-based anti-bullying programs on bullying, bullies’’ perspective, and victims’ perspective. Results of this study suggest that anti-bullying programs produce an effect that is positive and statistically significant but practically banal. It is hoped that this study will stimulate discussion in this area and provide an urge for identifying where we might have gone wrong. How should we view bullying and can we define it? Or are there many types of bullying that we cannot possibly create a single “prevention” program to “halt” it? With cyber-bullying occurring more than ever, is it possible to halt in-school-bullying?

School-based anti-bullying programs are not practically effective in reducing bullying or violent behaviors in the schools. This conclusion is likely to be disappointing for teachers, parents, and communities given the increased interest in targeting bullying and other violence in the schools. Given the noble, yet disappointing goal of reducing violence in the schools and the enormous financial and research effort devoted to developing anti-bullying programs, it would be useful to consider why these programs demonstrate such limited effectiveness. Are we seeing bullying differently, or is it that (as explained on previous papers) we facing the problem from a different perspective? Do we need to review what a bully is and how do they start even though research show that toddlers are naturally aggressive? Donald Herb (1997) and Tremablay & Nagic (2005). Several explanations are offered here, although further research would be necessary to truly understand this yet “inexplicable” behavior.

The first suggestion is that bullying, in particular (as opposed to more serious violence), is more advantageous to bullies than is nonbullying – we should understand this as bullying and “prevention” programs could possibly foster more violence behaviors rather than halting them. They might not be shown at school due to the consequences students might face, but this may transfer to outside violence. Although bullies are still perceived as insecure and, in effect, victims of their own aggression, research has suggested the opposite, yet some are still against this finding because research has also shown that some people might be seen hide themselves into projections of what they would like to be. On Carney (2010) words: “powerful people are better liars”. Here findings showed that powerful people shoulder shrugged less than less-powerful people.

Aside from aggressive and dominant personality traits, bullies have high self-esteem and are effectively normal children (Olweus, 1995). Bullying and violent behavior may, in many cases, be an effective strategy in climbing the dominant society among children at the expense of other children. As anti-bullying programs may encourage equality in problem solving that would involve bullies reducing their social dominance, there may simply be no incentive offered by these programs to attract bullies or violent children to follow them or be encouraged to participate in such activities. In other words, anti-bullying programs seem to only benefit victims by “halting” aggressive, and thus how are we really helping victims and more importantly what is happening with the aggressive peers is the are not incentivized for participating? As bullies or violent children see no personal benefit in following the program recommendations, they simply reject them. Nonviolent children are often seen trying to follow the program suggestions but may become frustrated when violent children do not. Thus, without effective incentives for bullies, there is little reason to believe that these programs are succeeding.

In conclusion, this study tried to examine the effects of school-based anti-bullying programs on bullying, bullies’’ perspective, and victims’ perspective. Results of this study suggest that anti-bullying programs produce an effect that is positive and statistically significant but practically banal. It is hoped that this study will stimulate discussion in this area and provide an urge for identifying where we might have gone wrong. How should we view bullying and can we define it? Or are there many types of bullying that we cannot possibly create a single “prevention” program to “halt” it? With cyber-bullying occurring more than ever, is it possible to halt in-school-bullying?

References

Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2006). Forgiveness, reconciliation, and shame: Three key

variables in reducing school bullying. Journal of Social Issues, 62(2), 347-370.

Carney, Dana (2010). Defend Your Research: Powerful People Are Better Liars.

Christopher J. F., Claudia SM, John K., JR and Patricia S. (2007). The Effectiveness of School-

Based Anti-Bullying Programs. Criminal Justice Review 2007 32: 401.

DeVoe, E., Dean, K., Traube, D., & McKay, M. (2005). The SURVIVE community project: A

family-based intervention to reduce the impact of violence exposures in urban youth. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 11, 95-116.

Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psychiatry, 1(4), 32-39.

Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What’s wrong? Aggressive

Behavior, 32, 528-539. Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., & Eitel, P. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk

youth. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29-49.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., & Eitel, P. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups

of at-risk youth. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29-49.

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Examining the relationship between low empathy and

bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 540-550.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001).

Bullying behav- iors among U.S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(16), 2094-2100.

Phillips, D. A. (2007). Punking and bullying: Strategies in middle school, high school, and

beyond. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(2), 158-178.Bierman, K. (2004). Peer rejection. New York: Guilford Press.

Sherman, L. W. (2000). The safe and drug-free schools act. Brookings Papers on Education

Policy, pp. 125-156. Taub, J. (2001). Evaluation of the Second Step Violence Prevention

Program at a rural elementary school.

Tremblay R, Nagin D, Séguin J, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo P, Boivin M, Pérusse D & Japel C.

(2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors.

Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2006). Forgiveness, reconciliation, and shame: Three key

variables in reducing school bullying. Journal of Social Issues, 62(2), 347-370.

Carney, Dana (2010). Defend Your Research: Powerful People Are Better Liars.

Christopher J. F., Claudia SM, John K., JR and Patricia S. (2007). The Effectiveness of School-

Based Anti-Bullying Programs. Criminal Justice Review 2007 32: 401.

DeVoe, E., Dean, K., Traube, D., & McKay, M. (2005). The SURVIVE community project: A

family-based intervention to reduce the impact of violence exposures in urban youth. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 11, 95-116.

Fishkind, A. (2002). Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psychiatry, 1(4), 32-39.

Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What’s wrong? Aggressive

Behavior, 32, 528-539. Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., & Eitel, P. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk

youth. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29-49.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., & Eitel, P. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups

of at-risk youth. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29-49.

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Examining the relationship between low empathy and

bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 540-550.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001).

Bullying behav- iors among U.S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(16), 2094-2100.

Phillips, D. A. (2007). Punking and bullying: Strategies in middle school, high school, and

beyond. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(2), 158-178.Bierman, K. (2004). Peer rejection. New York: Guilford Press.

Sherman, L. W. (2000). The safe and drug-free schools act. Brookings Papers on Education

Policy, pp. 125-156. Taub, J. (2001). Evaluation of the Second Step Violence Prevention

Program at a rural elementary school.

Tremblay R, Nagin D, Séguin J, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo P, Boivin M, Pérusse D & Japel C.

(2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed